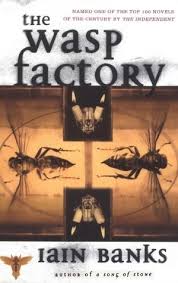

great Scottish writers - Iain Banks, The Wasp Factory.

Posted by celticman on Sun, 20 Aug 2017

Iain Banks (1985) The Wasp Factory.

I’ve read this book before and after reading it again I kinda remembered what happened in the end. But I didn’t appreciate it as a work of genius, the kind of thing I’d like to write, as I do now. Perhaps in the week that Philippa Gregory took time out slate other writers and make it clear she sees herself as the big I AM (https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2017/aug/14/philippa-gregory-lazy-and-sloppy-genre-writing-pornography), it’s good to look back at the deceased writer Iain Banks’s humility and what he says in the Preface to this book:

At the start of 1980 I thought of myself as a science fiction writer, albeit a profoundly unpublishable one. I’d wanted to be a writer since primary school and had started trying to write novels when I was fourteen, finally producing something loosely fitting that definition two years later; a spy story crammed with sex and violence (I still scorn the idea of only writing what you know about).

The Wasp Factory is science fiction fable in twelve chapters with elements of genetic, Frankenstein, social engineering. The narrator Frank Cauldhame, (Cold Home, Banks has a Dickensian ear for guttural names) aged sixteen, lives at home with his father in an isolated house in the East of Scotland where Iain Banks came from, separated from the fictiional village of Porterneil,by a bridge and the sea. Frank tells the reader his dad is ‘eccentric’, which in the nuanced Scottish way turns out to be something of an understatement. His only friend in a dwarf, Jamie, who Frank lets sit on his shoulders so he can see when they go to the mosh pit of the local boozer for a punk gig. The housekeeper Mrs Clamp is tiny, an ancient crone and his half -brother Eric is in the loony bin, a local legend for setting fire to dogs and trying to make the younger children in Porterneil eat worms and maggots, which he says has plenty of protein. Eric is the other, the threat from out there that threatens the safe space of (cold) home. All of the characters are in some way warped. The narrator is no exception, he tells the reader he is a serial killer, having murdered his younger brother, Paul, his elder cousin, and to balance up the cosmic equation, a younger female cousin. He has a very low opinion of females, equating them with bovine animals, such as sheep and cattle that have been dehorned and domesticated. He has no intention allowing that to happen to him. When Diggs, the policeman, comes to tell his father Eric has escaped from the asylum and is likely coming home Frank’s secrets and his dad’s, entwined, locked rooms and existence are threatened. Frank tells the reader,

‘[the house and land]was the centre of my power and strength, and also the place I had most need to protect’.

Frank has developed a series of rituasl to protect home. He uses the wasp factory he has constructed in the loft to read visions of the future. But he also consults the bones of Old Saul (related to Paul) in the bunker temple on the dunes of the beach. The Wasp Factory is a Gothic novel. Frank in the opening chapter, ‘The Sacrifice Poles,’ tells the reader about his rituals, ‘I had two poles on the dune. One of the poles held a rat head, with two dragonflies, the other a seagull and two mice.’

The Wasp Factory is a coming-of-age novel in which everyone is a liar, and protagonist, Frank Cauldhame, is as like a more cynical version of Holden Caulfield or Huckleberry Finn after they have sniffed glue and taken magic mushrooms and only he knows, or needs to uncover, the real truth, which is revealed in the denouement.

The Wasp Factory like any novel worth reading is a detective story and a thriller that asks questions of the reader. At its centre is played out the myth of Hermaphroditus and the logic of hermeneutics from the Greek ‘interpret’ with Frank’s father also acting as his mother, and his brother Eric, dressed in girl’s clothes from an early age with its suggestions of the mutability of gender. Eric’s divine madness, however, came from his humanity, from his studies as student doctor, a kind of extended post-traumatic-stress disorder played out away from the safety of home.

The Wasp Factory isn’t about wasps, but there is a sting in the tale. Everything changes and everything stays the same, like re-reading a book worth reading you see the world differently.

- celticman's blog

- Log in to post comments

- 4750 reads

Comments

I loved this book because I

I loved this book because I have a truly horrible sense of humour. Read it when young and when older. Good both times but more evident the second time that the author was young when it was his smash hit first novel. The other book of Iain Banks that I would read again is The Crow Road. I remember years ago wandering along Byres Road and noticing the name and the atmosphere of this big long tenement road. Watched the TV series too.

haven't read the crow road

haven't read the crow road else, but I will.

I shall look up the legend of

I shall look up the legend of Hermaphroditus.

I read The Wasp Factory a few

I read The Wasp Factory a few years ago and still have the copy. It is a clever book, and well worth a read, although not one I would ever wish to or be capable of writing. I do like Iain Banks as an author though, he is a favourite of mine, although I have only read a few of them. I particularly like some of his science fiction books about the Culture, which is the liberal and scientific culture which has spread through the galaxy (or galaxies?). Unfortunately they come up against an extreme religious civilisation (sound familiar?) which becomes a rival, and some very negative evils. He was a great author who went far beyond most peoples imagination.

As far as I remember he was

As far as I remember he was the first author to incorporate 'drones' in his sci fi, although maybe someone else came up with the idea before him.

I know he wrote his sci-fi

I know he wrote his sci-fi under the name Ian M Banks, but I haven't read any of them Kurt. But even reading the preface in the intoduction I got the impression he was humble about what he did and one of the writers I, for one, am glad left a legacy of wrting.