14 - The Father's Voice

By SoulFire77

- 100 reads

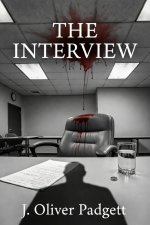

THE INTERVIEW

14: The Father's Voice

Q69. "Let's go back to your father."

The words landed in the quiet room like stones dropped into still water. Dale felt the ripples spreading through him—dread, exhaustion, the bone-deep weariness of a man who had been excavated for hours and still had more to give.

"You've mentioned him several times," Ms. Vance continued. "He seems important to you. Central, even."

"He was my father."

"That's not the same as being important. Many people have fathers who aren't central to their lives. But yours—" She glanced at her notes. "You became him, you said. You're terrified that you became him. That suggests a significance beyond the biological."

Dale was quiet for a moment. The clock on the wall still showed 3:47. The water stain on the ceiling had spread further, its brown edges creeping toward the corners of the room. The air tasted stale, recycled, like it had been breathed too many times.

"He was the model," Dale said finally. "The template for what a man was supposed to be. Work hard. Provide for your family. Don't complain, don't ask for help, don't show weakness. He never said any of that out loud—he didn't have to. He just lived it, every day, and I watched him, and I learned."

"What did you learn?"

"That work was everything. That a man's worth was measured in what he could do, what he could provide. That feelings were—" He searched for the word. "Irrelevant. Distractions. You did the job. You came home tired. You got up and did it again. That was the whole vocabulary."

"And you adopted that vocabulary."

"I didn't know there was another one."

Q70. "Tell me about the last time you saw him."

Dale closed his eyes. The hospital room assembled itself in his memory—the beige walls, the fluorescent lights, the machines beeping their steady rhythms. His father in the bed, smaller than he'd ever seemed, the strength that had defined him worn down to nothing.

"It was two weeks before he died. He'd had the first heart attack, and they were running tests, talking about surgery. I drove down from Greensboro—three hours to Kinston—and sat with him for the afternoon."

"What did you talk about?"

"Nothing." The word came out flat. "We sat there, and the TV was on, and we watched some game show. We didn't talk. We never talked. We just—existed in the same space. That was the closest we got to intimacy."

"Did you know it would be the last time?"

"No. I thought—" He swallowed. "I thought there would be more time. There's always supposed to be more time. But two weeks later, he was in the Walmart parking lot, and—" He stopped. "And there wasn't more time. There was no time at all."

Q71. "What were his last words to you? Not his last words—his last words to you."

Dale tried to remember. The hospital room. The game show on TV. His father's face, turned toward the screen. What had he said? What had been the last thing his father ever said directly to him?

"He said—" Dale frowned, concentrating. "He said something about—about being careful on the drive home. Or—" The memory was slippery, refusing to hold its shape. "He said something. I know he said something."

"But you don't remember what."

"I remember—" He grasped for it. His father's voice, forming words, the last words they would ever exchange. But the voice was gone—he'd noticed that earlier, the way his father's voice had faded—and without the voice, the words themselves were—

"I don't remember," he admitted. "I can't hear him anymore. And without the sound, I can't—I can't find the words."

"That must be frustrating."

"It's—" He didn't have a word for what it was. Terrifying. Devastating. Like watching a piece of himself dissolve. "I knew what he said this morning. When I was getting ready. I could hear him in my head, his voice, his words. And now—"

"Now?"

"Now there's just silence where he used to be."

Q72. "What did his hands look like?"

The question was unexpected—a turn toward the physical, the concrete. Dale reached for the memory.

"They were—" He could see them, his father's hands. "Big. Bigger than mine. The fingers were thick, the knuckles swollen from years of work. He had calluses on the palms that never went away, even after he stopped doing the heavy labor. And his nails were always—" He stopped. "Were always—"

The image was fading. He could still see the shape of the hands, the general form. But the specifics—the calluses, the swollen knuckles—were becoming vague, impressionistic.

"Always what?"

"I'm sorry." He shook his head. "The picture isn't—I can see his hands, but I can't see the details anymore."

"It's okay." Ms. Vance's voice was gentle. "You're tired. The details slip."

"They shouldn't slip. This is my father. I should be able to—"

"You should be able to what, Dale?"

"Hold onto him." The words came out cracked, broken. "He's already dead. He's been dead for six years. And now I'm losing him again. Piece by piece. The voice. The hands. The last words. What's going to be left? What's going to be left of him when—"

He couldn't finish. The question was too large, too terrible.

Q73. "His voice—can you demonstrate it for me?"

Dale stared at her. "What?"

"Your father's voice. The way he sounded when he spoke. Can you demonstrate it?"

"I—" He'd done it before, hadn't he? Imitated his father's gruff Piedmont drawl, the flat vowels and clipped consonants. At family gatherings, he'd done it for laughs—you work too hard, boy—and everyone had said he sounded just like Walter. He knew his father's voice. He'd carried it in his head for fifty years.

He opened his mouth to demonstrate.

Nothing came.

He could feel the shape of it, the intention. His throat prepared to make the sound, his mouth formed around the words. But the voice itself—the actual timbre, the specific quality that had made it his father's—

"I can't." The admission came out in his own voice, small and lost. "I know what he sounded like. I know I know. But when I try to—"

"It's not there."

"It's not there." Dale felt something crack in his chest, some final support giving way. "Oh God. It's not there. He's—I've lost him. I've lost his voice completely."

The room was silent. The clock showed 3:47. The water stain spread across the ceiling. And Dale sat in his chair and felt the absence of his father's voice like a hole in the center of his chest.

Then Ms. Vance spoke.

"You work too hard, boy."

Dale's head snapped up.

The voice that had come out of her mouth—

"You're gonna end up just like me."

It was his father's voice.

Not an imitation. Not an approximation. It was Walter Kinney's voice, the exact sound Dale had been trying to find—the gruff Piedmont drawl, the flat vowels, the weariness that lived beneath every word.

"What—" Dale's own voice came out strangled. "What did you—how did you—"

"You told me." Ms. Vance's voice was her own again, neutral and professional. "Earlier in the interview. You told me what he said to you. I was just repeating it."

"That wasn't—" He couldn't breathe properly. His chest was too tight. "That was his voice. That was exactly his voice. How did you—"

"I have a good ear for accents." She smiled, that professional smile. "I'm sorry if it startled you. I didn't mean to—"

"Say it again."

The words came out before Dale could stop them.

"I'm sorry?"

"Say it again. His voice. I want to hear it again."

Ms. Vance was quiet for a moment. Her eyes held his, that not-quite-color, that infinite patience.

"I don't think that would be helpful, Dale."

"Please." He heard the desperation in his own voice and didn't care. "I can't hear him anymore. I've tried and I can't—but you can. You have his voice. Please. Just—just let me hear it one more time."

"Dale—"

"Please."

The silence stretched. The room held its breath. And then Ms. Vance spoke, and the voice that came out was Walter Kinney's voice, and Dale felt his heart break all over again.

"I'm proud of you, son."

The words hung in the air. Words his father had never said. Words Dale had waited his whole life to hear. And they were coming from a stranger's mouth, in a voice Dale could no longer produce himself.

"He never—" Dale's eyes were wet. He couldn't stop them. "He never said that. He never said that to me."

"I know." Ms. Vance's voice was her own again. "But I thought you might want to hear it anyway."

"Why—" He wiped his eyes with the back of his hand. "Why would you do that? Why would you say something he never said, in his voice, to me?"

"Because I can." She picked up her pen, made a note on the legal pad. "And because you needed to hear it. Even if it wasn't real."

Dale stared at her. At her calm face, her patient eyes, her pen moving across the paper. He should be angry. He should be outraged that she'd used his father's voice, that she'd put words in a dead man's mouth, that she'd—

But he wasn't angry. He was grateful. Grateful to have heard that voice one more time, even coming from somewhere wrong. Grateful for the words, even if they were lies.

"Thank you," he said. His voice was barely above a whisper.

Ms. Vance looked up from her notes. Something flickered in her expression—satisfaction, perhaps, or something deeper.

"You're welcome," she said. "Now. Let's continue."

Q74. "What do you think he saw when he looked at you?"

Dale was quiet for a long moment. The question required him to imagine his father's perspective, to see himself through Walter Kinney's eyes. He'd avoided doing that for his whole life. It was too painful, the picture that emerged.

"Disappointment," he said finally. "I think he saw disappointment."

"Why?"

"Because I wasn't—" He searched for the words. "I wasn't enough. I went into the same work he did, but I never had his strength. His endurance. He could work a double shift and come home ready for more. I'd work a regular day and be wrung out. He looked at me and saw—a weaker version of himself. A copy that didn't quite take."

"You think he compared you to himself?"

"I think that's all he knew how to do. He didn't have—he didn't have the vocabulary for anything else. So he watched me struggle, and he saw his own struggles reflected back, and he wondered why I couldn't handle it the way he did."

"Did he ever say that? That you were disappointing?"

"He didn't have to." Dale looked at his hands, the age spots and the ghost calluses. "I could see it in the way he looked at me. The way he'd watch me work and then take over, not saying anything, just showing me that he could do it faster, better. Every time he did that, it was—it was a verdict. A judgment."

"And now that he's gone?"

"Now—" Dale swallowed. "Now I'll never know if I was wrong. If what I saw in his eyes was really disappointment, or if it was something else. Love, maybe. Worry. The kind of attention that looks like judgment when you're too scared to see it clearly."

"Which would you prefer to believe?"

"I don't know." The admission hurt. "I've spent so long believing he was disappointed that I don't know how to believe anything else. And now—now I can't even hear his voice in my own head. How am I supposed to know what he thought of me when I can't even remember what he sounded like?"

Ms. Vance was watching him with that absolute attention, that stillness that seemed to absorb everything he said.

"You remember one thing," she said quietly.

"What?"

"The words. 'You work too hard, boy. You're gonna end up just like me.' Those were his last words to you. The ones you couldn't remember before."

Dale blinked. She was right. He couldn't hear the voice anymore—not on his own—but the words were there. The words had come back when she'd spoken them.

"Is that—" He hesitated. "Is that a warning? Or a—a wish?"

"What do you think?"

"I think—" He closed his eyes. "I think he was trying to tell me something he couldn't say any other way. That he was worried about me. That he didn't want me to end up like him—worn out, used up, dying in a parking lot with the engine still running. I think it was the closest he could get to saying—"

"To saying what?"

"I love you." The words came out soft, almost inaudible. "I think that's what he was trying to say. In the only language he knew."

The room was quiet. The clock showed 3:47. The water stain spread across the ceiling like something alive, something hungry.

And Dale sat in his chair and let himself believe, for just a moment, that his father had loved him after all.

Even if the proof had come from a stranger's mouth.

Even if the words had never actually been spoken.

Even if he could no longer hear the voice that should have said them.

- Log in to post comments