04 - Behavioral Territory

By SoulFire77

- 89 reads

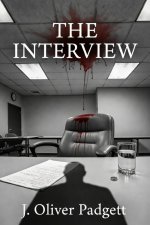

THE INTERVIEW

4: Behavioral Territory

Q15. "Tell me about a time you had to deal with a difficult coworker."

The question was familiar, comfortable. Dale had a story for this one, polished smooth by repetition.

"At Consolidated, there was a guy named Ray Hubbert. Shift lead on second shift, been there fifteen years when I arrived. He didn't like me from day one—saw me as a threat, I think, even though we were running different shifts. He'd leave messes for my crew to clean up, forget to pass along information. Passive-aggressive stuff."

"How did you handle it?"

"Tried the direct approach first. Sat down with him, man to man, said I wasn't there to step on his toes. Didn't work. He just got more subtle about it." Dale paused, remembering. Ray's face was still clear in his mind—the heavy jowls, the permanent squint, the way he'd smile while twisting the knife. "So I changed tactics. Started documenting everything. Every time information didn't get passed along, every time equipment was left in the wrong place. Built a paper trail. Then I went to the ops manager with a proposal: weekly handoff meetings between shifts, formalized protocols for transition. Made it about process, not personality."

"And that worked?"

"It did. Ray couldn't sabotage what was written down and witnessed by management. Once he realized I wasn't going to fight him on his level, he backed off. We never became friends, but we became functional." Dale allowed himself a small smile. "Sometimes that's the best you can get."

Ms. Vance wrote, nodded. "You turned a personal conflict into a systemic solution. That's sophisticated thinking."

"I've learned that most problems aren't really about the people. They're about the systems that let the problems happen. Fix the system, the people usually sort themselves out."

Q16. "Usually," she repeated. "But not always?"

"Not always. Some people are just—" He searched for the diplomatic word. "—determined to be difficult. But those are rare. Most of the time, people act badly because the situation allows them to. Change the situation, change the behavior."

"Do you believe that about yourself as well? That your behavior is shaped by your circumstances?"

The question felt like a step sideways, away from the standard script. He considered it.

"I think everyone's shaped by their circumstances. That's not an excuse—we're still responsible for our choices. But it's naive to pretend we're making those choices in a vacuum."

Ms. Vance tilted her head slightly. "What circumstances have shaped you, Dale?"

"I—" He paused. This wasn't a behavioral question anymore. This was something else. "I'm not sure what you're asking."

"I'm just curious." Her pen was still. Her eyes were on him, and in the flat fluorescent light they looked almost colorless, like water, like glass. "You've been very thorough about your professional history. I'm wondering about the personal circumstances that made you who you are."

"That's a big question."

"We have time."

He glanced at where a clock should be. Bare wall. No way to know how long they'd been talking, how long was left.

"Maybe we could come back to that," he said. "If you don't mind."

"Of course." She smiled, and the moment passed. "Let's continue with the behavioral questions."

Q17. "Tell me about a situation where you disagreed with a supervisor's decision."

Familiar ground again. He had a story for this too.

"At Morrison, during my operations manager years. The VP of logistics wanted to cut our quality control process in half—said it was slowing throughput and the error rate didn't justify the time investment. I disagreed. The error rate was low because of the QC process, not in spite of it. Cut the process and you'd see that rate climb within weeks."

"What did you do?"

"Ran the numbers. Pulled three months of data, showed him exactly what each QC checkpoint was catching, calculated the cost of those errors if they'd made it to the customer. Returns, replacements, lost accounts. Made it clear that the throughput gains would be eaten up by downstream costs within a quarter."

"And he listened?"

"Didn't like it—nobody likes being told they're wrong—but he couldn't argue with the math. The QC process stayed."

"You seem comfortable with confrontation."

Dale shook his head. "I wouldn't say that. I don't enjoy disagreeing with people, especially people who have power over my job. But I've learned that avoiding conflict just delays it. Better to have it out early, with data, than to let a bad decision play out and deal with the wreckage."

"Even when it puts you at risk?"

"Even then." He met her eyes. "I've been fired for being right before. Not at Morrison—somewhere else. I'd rather be fired for speaking up than employed for staying quiet."

"That's admirable." She wrote something. "And unusual. Most people choose security."

"Most people don't have thirty-two years of watching what happens when nobody speaks up."

Q18. "Tell me about a time you met a tight deadline with limited resources."

Another story. The ice storm at Morrison, the scramble to save the refrigerated inventory. He told it well—he'd told it many times—and Ms. Vance listened with that absolute attention that made him feel heard, seen, understood.

But something was different now. Something had shifted in the room, so subtle he couldn't name it. The air felt thicker somehow. The silence between her questions felt heavier. The fluorescent lights buzzed at a frequency that seemed to burrow into his skull, and behind his eyes a dull ache was building.

He kept talking. Answering. Performing.

Q19. "Give me an example of a time you had to adapt to a major change at work."

He talked about the Morrison acquisition. The new systems, the new management, the wholesale transformation of everything he'd spent a decade building. He talked about learning to speak a new language—the language of metrics and efficiency and shareholder value—while trying to protect the people and processes that actually made things work.

Ms. Vance nodded, wrote, asked follow-ups. The pen scratched against paper. The coffee cup steamed, untouched.

Dale's mouth was dry. He'd finished the water glass without noticing—when had he done that?—and now he sat with an empty glass and a throat that felt like sandpaper.

"Would you like more water?" Ms. Vance asked, as if she'd heard the thought.

"Please."

She didn't move to get it. Just looked at his glass, and then the glass was full again—cold, sweating, condensation pooling on the laminate surface.

He stared at it.

"Is something wrong?"

"No, I—" He reached for the glass. The water was there. It had always been there. He must have—he must not have finished it after all. Must have misjudged how much was left. "No. Nothing's wrong."

He drank. The water was cold enough to hurt his teeth.

Q20. "Tell me about a time you went above and beyond for a company that didn't recognize it."

He laughed, short and humorless. "How much time do you have?"

"As much as you need."

So he told her. The hurricane in 2018, three days at Morrison coordinating emergency protocols, sleeping on a cot in the break room, making sure the building and inventory and people were safe—and then being told by corporate that the overtime wasn't approved and he should have cleared it first. The training program he'd developed on his own time, the one that reduced new hire turnover by thirty percent, adopted company-wide without so much as a thank-you. The nights he'd stayed late and the weekends he'd come in and the holidays he'd worked, all of it disappearing into the machinery without acknowledgment.

He told her more than he meant to. The words kept coming, a tide of accumulated grievance he hadn't realized he'd been holding back.

"You feel undervalued," Ms. Vance said when he finally wound down.

"I feel realistic." He took a breath, steadied himself. "I know how this industry works. I know what companies are willing to invest in their people and what they're not. I'm not expecting gratitude. I'm just expecting—" He stopped.

"What are you expecting, Dale?"

"Fair compensation for work performed. That doesn't seem like too much to ask."

"It shouldn't be." She wrote something on her pad. "But it often is."

"Yes." He was tired, suddenly. The talking, the performing, the careful navigation of questions designed to reveal weakness while appearing to reveal strength. "It often is."

Q21. "Tell me about training someone who didn't want to learn."

He had a story. He told it. The words came out in the right order, hit the right beats, made the right points. But he was operating on autopilot now, some part of him watching from a distance while the performance continued.

The headache was worse. A dull pulse behind his eyes, steady as a heartbeat. His back had settled into a constant low throb. His hands, resting on the table, had a faint tremor he didn't remember having that morning.

He finished the story. Ms. Vance nodded, made her notes, asked the next question.

Q22. "Describe a time you had to make a decision with incomplete information."

He answered. His voice sounded normal to his own ears—confident, practiced, professional. But underneath, something was itching. The water glass that had refilled itself. The coffee cup that never emptied. The room that had no clock, no windows, no way to mark the passage of time.

On the table in front of Ms. Vance, the coffee still steamed. He watched it, waiting to see her lift the cup, take a sip, do something normal. She didn't. The cup sat there, steam rising in thin spirals, and the level never changed.

He looked away.

Q23. "Looking at your career overall, what would you say is your greatest weakness?"

The trap question. Every interview guide warned about it. Have an answer ready, but make it a weakness that's really a strength. "I work too hard." "I'm a perfectionist." Something that sounds humble but actually makes you look good.

He opened his mouth to give the prepared answer—something about taking on too much, needing to delegate more—and what came out instead was:

"I don't know when to quit."

Ms. Vance's pen stopped.

"I mean—" He tried to recover, to steer back to the script. "I mean I'm persistent. I keep working on problems even when—"

"That's not what you meant."

It wasn't. It wasn't what he'd meant at all.

"I stay too long," he heard himself say. "In jobs that are killing me. In situations that aren't going to get better. I keep thinking if I just work harder, if I just give a little more, it'll turn around. But it doesn't turn around. It just takes more. And I keep giving it, because I don't know how to stop."

The room was quiet. The HVAC had gone silent again. Even the fluorescent buzz seemed muted, distant.

"That's very honest," Ms. Vance said.

"I didn't mean to—" He stopped. What was happening to him? This wasn't how you did an interview. This wasn't how you presented yourself. "I'm sorry. I'm more tired than I realized. That came out wrong."

"It didn't come out wrong." Her voice was gentle now, almost kind. "It came out true. There's a difference."

She closed her legal pad. Set down her pen. Folded her hands on the table in front of her.

"I think," she said, "we've covered the behavioral questions thoroughly. Now I'd like to move into something more personal. Questions about who you are, not just what you've done." She paused. "Are you comfortable with that?"

The door was behind him. He could feel it there, patient and present. The way out. The way back to the waiting room, the parking lot, the world outside this cold beige box with its flickering lights and its impossible coffee cup and its water stain spreading slowly across the ceiling.

He should leave. Something in him knew he should leave.

But what would he tell Linda?

The question surfaced from somewhere practical and damning. What would he tell her when he walked through the door? That he'd left in the middle of the interview? That he'd gotten spooked by a coffee cup that didn't empty, by a water glass that seemed to refill itself, by questions that cut a little too close? That he'd thrown away his thirteenth chance because something felt off?

She'd look at him with those careful eyes. She'd say it was fine, of course it was fine, he'd made the right choice. And underneath the words he'd hear what she was really thinking: Another failure. Another excuse. Another reason to wonder.

He needed this job. They were fourteen days late on the mortgage. The credit card was maxed. His daughter's cracked face was pressed against his thigh, and his wife was at home saying you've got this to an empty kitchen.

"Of course," he said. "I'm comfortable."

Ms. Vance smiled. Something in the smile was different now—warmer, more intimate. Like a door opening onto a room he couldn't quite see.

"Good," she said. "Then let's continue."

- Log in to post comments