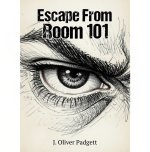

03 - Peter Harmon (1)

By SoulFire77

- 55 reads

Chapter 3: Peter Harmon

Peter Harmon worked in the Historical Archives section, three floors

below the Records Department. Arthur had known him for six years---or it

might have been seven. Time blurred in the Ministry, one day folding

into the next, the years accumulating like sediment at the bottom of a

glass that was never emptied.

They had met in the canteen, two men reaching for the same cup of

synthetic coffee at the same moment. A small collision, an apology, a

nod of recognition. The coffee had sloshed over the rim and onto

Arthur's fingers, lukewarm and bitter-smelling, leaving a faint stain

on his skin that he rubbed at for the rest of the morning. The kind of

encounter that happened a hundred times a day in the Ministry and was

immediately forgotten.

But Arthur had not forgotten Peter. And Peter, it seemed, had not

forgotten Arthur.

It began with glances. A look across the canteen that lasted a fraction

of a second longer than necessary. A nod in the corridor that carried

some weight beyond mere acknowledgment. The small recognitions that

passed between people who had noticed each other noticing.

They did not speak. Not at first. Speaking was dangerous---words could

be overheard, recorded, analyzed. But glances were deniable. A glance

was just a glance. Two men looking at each other in a crowded room

proved nothing.

The glances accumulated. Over weeks, over months, they developed a

vocabulary. A slight raise of the eyebrows: Did you see that? A small

shake of the head: Don't look now. A moment of eye contact held just

past the point of comfort: I know. I see it too.

Arthur did not know what Peter saw. He did not know what doubts moved

behind those careful eyes. But he knew that Peter was watching the same

world he was watching, and seeing something other than what the Party

said was there.

That was enough. In the Ministry of Truth, that was everything.

#

Their first real conversation happened in the men's lavatory on the

fourth floor.

It was not planned. Arthur had gone to relieve himself; Peter had been

washing his hands at the basin. The room was empty except for them---a

rare occurrence, a window of perhaps thirty seconds before someone else

would enter. The tile floor was damp, the grout between the tiles

stained a yellowish brown. The single light fixture buzzed overhead,

casting everything in a flat, shadowless white.

Peter looked up from the basin. His eyes met Arthur's in the mirror.

"The chocolate ration," Peter said. His voice was barely above a

whisper.

Arthur's hands went still at his sides.

"Thirty grams," he said.

"It was thirty grams last month."

"Before the reduction."

"Before the increase."

They looked at each other. The words hung in the air between

them---impossible words, dangerous words, words that acknowledged what

could not be acknowledged. The light buzzed. Water dripped from the tap

Peter had not quite closed, each drop striking the porcelain basin with

a sound like a small clock ticking.

The door opened. A clerk from the Fiction Department entered, nodding to

them both. Peter turned off the water and dried his hands on the rough

cloth that hung beside the basin. Arthur stepped to the urinal.

Nothing had happened. Two men had exchanged pleasantries about the

chocolate ration while washing their hands. Perfectly normal. Perfectly

innocent.

But Arthur's hands were shaking when he held them under the tap, and

when he looked at himself in the mirror, his face was the color of old

paper.

#

After that, they found ways to speak.

Never for long. Never in places where they might be observed. The

fourth-floor lavatory became their regular meeting point---not by

arrangement, but by a pattern that emerged without being discussed.

Arthur would go there at 10:15 each morning. Peter would arrive a few

minutes later. If the room was occupied, they would nod and leave. If it

was empty, they would have perhaps a minute of whispered conversation

before someone else entered.

A minute was enough. A minute was more than Arthur had ever had with

anyone.

They spoke in fragments, in implications, in the spaces between words.

Peter had noticed the shoe---the same shoe, thrown during each Two

Minutes Hate, collected and redistributed. Arthur had noticed the

production figures---the same increases announced repeatedly, the

baseline constantly adjusted, the triumph that never ended because it

never began.

They did not call these things doubts. They did not use words like lies

or manipulation or control. They simply described what they had seen,

and let the other draw conclusions.

Peter understood. Peter saw. Peter was awake in a world of sleepwalkers.

And Peter, Arthur realized gradually, was the only person he might call

friend.

#

Peter Harmon was forty-three years old, or so he claimed. His face was

lined in ways that suggested either hard years or premature aging---the

distinction was difficult to make in Oceania, where everyone aged faster

than they should. He had thin brown hair that was beginning to retreat

from his forehead, and a small mole on his left cheek that Arthur had

memorized without meaning to.

He walked with a slight hitch in his step---an old injury, perhaps, or

simply the way his body had learned to move. Arthur could recognize that

walk from across the canteen, from the far end of a corridor, from a

glimpse through a doorway. The rhythm of it was distinctive: step,

slight pause, step, slight pause. A signature written in movement.

Peter had a habit of holding his pencil between two fingers and tapping

it against his palm when he was thinking. The pencil was Ministry-issue,

identical to every other pencil in the building, but Peter's way of

holding it was his own. Arthur had watched him do it a hundred times

during the Two Minutes Hate, the pencil tapping out a quiet rhythm

against his skin while his face performed the required fury.

These details were dangerous to know. These details meant that Arthur

had been watching Peter with an attention that went beyond casual

observation. If the Thought Police ever asked what he knew about Peter

Harmon, these details would betray him.

Arthur knew them anyway. He could not stop himself from knowing them.

#

The contraband appeared three months into their acquaintance.

Peter brought it to the fourth-floor lavatory in his pocket, wrapped in

a scrap of newspaper. He pressed it into Arthur's hand without a word,

and Arthur felt the shape of it through the paper---small, hard,

unfamiliar. The newspaper was damp from Peter's palm. The ink had begun

to smear.

"Don't open it here," Peter whispered. "Tonight. In your flat."

Then he was gone, out the door before Arthur could respond, leaving

Arthur standing at the basin with something forbidden in his hand.

Arthur put it in his pocket. The weight of it was negligible---lighter

than the speakwrite dial, smaller than a coin. He walked back to the

Records Department with his pulse loud in his ears, certain that

everyone could see the bulge in his overalls, certain that the

telescreen had somehow observed the exchange.

Nothing happened. No one looked at him. The day continued as days always

continued, and Arthur spoke his corrections into the speakwrite and ate

his lunch in the canteen and walked home through the gray streets and

climbed the seven flights to his flat.

Only then, with his back to the telescreen and his hands hidden in his

lap, did he unwrap the newspaper.

It was a photograph.

Black and white, faded, creased from years of folding. The image showed

a street scene---a row of shops, a group of people walking, a sign above

a doorway that read WOOLWORTH'S in letters Arthur did not recognize.

The edges of the photograph were soft with handling, worn smooth by many

fingers over many years.

The street was clean. The buildings were intact. The people were

smiling.

Arthur stared at the photograph. His hands had begun to tremble.

He had never seen a street like this. He had never seen buildings

without bomb damage, without shored-up walls and patched windows. He had

never seen people walking with that easy, unguarded posture---as if they

had nowhere particular to go, as if time belonged to them.

The sign said WOOLWORTH'S. Arthur did not know what a Woolworth's was.

The word had no meaning in Newspeak, no entry in any dictionary he had

ever seen. It was a word from before---from the time that existed only

in fragments, in memories that could not be trusted, in photographs like

this one that should not exist.

He turned it over. On the back, in faded pencil, someone had written:

London, 1952.

1952. Thirty years ago. Or forty. Or yesterday. Time was difficult in

Oceania.

Arthur looked at the photograph for a long time. The clean street. The

whole buildings. The people who were smiling. A woman in the foreground

wore a hat with a small feather. A man carried a parcel under his arm,

brown paper tied with string. They looked like people who expected to be

alive tomorrow.

Then he folded it carefully, matching the creases to the creases that

were already there, and put it in his pocket, next to the speakwrite

dial.

#

"Where did you get it?" Arthur asked the next day, in the fourth-floor

lavatory.

Peter shook his head. "Better not to know."

"But---"

"It's from the Archives. That's all I'll say. Things get misfiled.

Things end up in the wrong boxes. The system isn't perfect."

The system isn't perfect. The words hung between them, heavy with

implication.

"Why?" Arthur asked. "Why give it to me?"

Peter was quiet for a moment. His hand went to his pocket, and Arthur

knew he was touching something there---another photograph, perhaps, or

some other piece of the past that should have been destroyed.

"Because you see it," Peter said finally. "The cracks. The places

where the surface doesn't match what's underneath. I've been watching

you for months, and you see it. You're the only person I've met in ten

years who sees it."

Arthur's throat was tight. "I see a shoe," he said. "I see a

chocolate ration. I don't see---"

"You see enough." Peter's eyes met his. "That's the only thing that

matters. You see enough to know that what they tell us isn't what is."

The door opened. A young woman from the Fiction Department entered,

barely glancing at them. Peter turned on the water, rinsed his hands,

dried them on the rough cloth that hung beside the basin.

"Same time tomorrow," he murmured as he passed Arthur on his way out.

Arthur nodded. His hand was in his pocket, touching the photograph

through the fabric of his overalls.

London, 1952. A world that had existed. A world that had been erased. A

world that was still there, folded in his pocket, proof that the Party

could not destroy everything.

#

(Cont.)

- Log in to post comments