Xion Island Zero: Chapter 28

By Sooz006

- 533 reads

The wind sweeping through the cemetery was uncommitted, the kind that rustled hems and ribbons but didn’t disturb the dead. Even the weather managed to bow its head in respect of the children.

They’d asked the public to respect the need for a private funeral, but the police still turned hundreds of curious gate crashers away at the Schneider Road roundabout down the road from the crematorium gates. They closed all access roads.

Four horse-drawn hearses rolled slowly up the curved drive, their black paint gleaming with recent rain. A single white lily lay across each coffin. Although he couldn’t see the gold lettering etched into the plaques through the oblong viewing pane, Nash knew what they said: Iris Taylor, Carrie Taylor, Lorraine Taylor, and Belinda Taylor. Three generations, all killed in the same week. There would be no more birthday parties, and they’d eaten their last Sunday dinners. The family line had been almost wiped out. There was only Alan Taylor left to protect and Bernstein to put away for a long time. Nash was an only child. Both of his parents were gone, and it saddened him that he was the last of his line, too. Kelvin once brought up the subject of adopting before they got too old, but Nash soon shot that one down. The thought of being a dad gave him the jitters. He said he couldn’t relate to young people, but had no idea how good he was with them.

He dragged his mind back to the job as Alan Taylor stepped out of a limousine. He was wide open and ripe for the picking. Nash had so many heavies on standby that people would find it easier to take down the king.

Behind the horses and two black limousines, all funded by local business, Getaway Travel, people spilt from cars. The people allowed in had been vetted as knowing at least one family member. Black clothing was the order of the day, despite two of the dead being children. There were no bright colours here. The coats flapped in the wind like crows—a murder of crows, were ravens kinder? A woman’s sob broke the stillness, but Nash didn’t look to see who it was. Grief was everywhere. It swelled in the eyes of strangers and the clasped hands of classmates. It was in the twitch of a father’s jaw.

Nash checked his coat for lint. His funeral clothes saw a lot of services, and he refused to carry one family’s grief into the next funeral on his clothes. He attended at least one service per case, and they made his gait heavier. After each case closed, his suit and greatcoat were meticulously dry-cleaned regardless of whether they needed it. Dry-cleaning was bad for the environment, and most shops offering the service had closed. There was only one company in the area now, and that was on Walney Island. Soon it would go too. He didn’t know what he’d do about his suit then.

Nash shook his head as mundane thoughts cracked through his funeral fog. The weight of the coffins varied, but, as far as memorials went, he’d seen it all. Each one broke his heart, but standing around in the cold still irritated him. Autumn had turned to winter, and he couldn’t believe he was getting married in six weeks. A December wedding had seemed romantic in the planning stages.

He watched the procession move forward. Alan stood apart, an easy target by design. His coat looked thick over a bulletproof vest, but that was only to Nash’s eye. Nobody else would notice. Alan’s collar was stiff with starch, and a tremor in his hands shook his order of service. He was pale, struggling to stand upright, and wore grief like a straitjacket. It was foreign to him and looked too tight around the chest.

Alan approached the row of hearses slowly, as though distance could soften the agony. Behind him, a woman in another black coat walked with a stiff spine. Her face was drawn and lined with the anger that came from years of control.

She was Hilary Strickland, Carrie’s mother. A difficult woman, Nash had interviewed her at the station after her daughter’s death. She spoke to him before going into the crematorium.

‘I don’t approve of this joint funeral,’ she said. ‘I only agreed because the police insisted it would be safer. And because I’m not stupid. I know consulting me regarding the decision was only paying lip service. It would have been taken out of my hands anyway. I’m her mother, but he’s still listed as next of kin. How is that right, inspector?’ She nodded at Alan and pulled a face of disapproval.

Nash let her talk.

She hadn’t cried. Not at the station, or before the funerals, as they discussed her murdered daughter and granddaughters. But Nash saw the way grief tore at her shoulders and pulled them lower, despite her beautiful posture. He wondered if she’d been a dancer. He knew from witnesses that this lady lived by control. The kind she exerted over others, and the share she took to govern herself. She was stoic from learning to breathe around too much loss.

‘I warned her about him. Alan was always reckless—rootless, too. He grew up wild. And after the unfortunate episode, that was down to him because my Carrie had been brought up right, I told her to put it behind her and start over, but would she listen? He landed back like a bad smell a year later, and just picked up from where he’d left her stranded.’

Nash said nothing because the coffins were rolled from the hearses, and Hilary Strickland stepped closer to Alan. There was a coldness between them with the anchorage of decades. Neither spoke for a long time as they watched their loved ones being taken into the church.

‘We should go in,’ Alan said. He was crying.

‘Not until my babies are in place,’ she replied.

They waited, and Nash stood at a discreet distance, but close enough to hear their conversation. ‘This is down to you. Carrie wanted to keep the child, but I wouldn’t let her. I thought I was saving her life, and now look. It should be you in that coffin, and I hope I see it before I die.’

Alan’s voice was quiet. ‘We made our choices. And we all carry the blame.’

Her voice was emotionless, and Nash wondered at which point this woman would break. ‘I suppose we do,’ she said, ‘some more than others. But it doesn’t bring them back. No apology or backwards wish ever can. She should have had an abortion.’

Hilary snapped at him again as she spoke. ‘Give me your elbow, people are looking.’ As she took it, she looked at it as though it was filthy before taking it. The three of them walked into the service together, Hilary, Alan and Grief.

Nash took a pew at the back with a clear view of the room. The service began, and the priest stepped forward. Nash sighed, settling in for a long one. Priest-attended services were rare these days. Most people went for the anonymous celebrant. But this guy’s voice was gentle, the kind used for bruised children and rooms filled with somebody else’s sorrow.

‘Today, we say goodbye to four precious lives. Iris, a mother and grandmother. Carrie, a daughter, who died protecting her children. And Lorraine and Belinda, two beautiful, lively girls whose futures were stolen almost before they began.’

The officers were all in plain clothes. There were no uniforms to draw the eye. The protection was subtle, but it was there. They had snipers, a bodycam on the priest, and unmarked cars lining the cemetery’s edge. But none of it mattered. Because this tragic hour was about loss. The protection came too late.

He watched as Lorraine’s classmates put white roses near her coffin. They wept. One girl tried reading a poem, but she broke down halfway through, her voice cracked on the words. She’d never be innocent again.

Belinda’s teddy was tucked between the handles of her casket. He was worn with matted fur from years of love. The traditional black-sewn mouth looked sad. Her cousin had brought it to stop Belinda feeling frightened, and Nash had to turn away for a moment.

The air smelled of incense. They were going all-out on the Catholic funeral, though they had agreed on the modern norm of cremation rather than burial. Somewhere in the distance, a dog barked. Then there was silence again during a moment of head-lowered contemplation. Nash took the opportunity to look around.

But when the choir sang, he closed his eyes against the emotion. Their harmony was imperfect but human. It sounded like people doing their best in the face of something senseless. The soloist sang through tear-streaked cheeks.

He opened his eyes when Alan took the rostrum. The broken man looked lost in time, as if he couldn’t find the door to the past.

He spoke about Carrie and the girls, and Nash was pleased when he didn’t leave Iris out of his eulogy. He could see how Alan struggled, but he didn’t give up. This was his duty and the last thing he’d ever do for his family, so he fought through his sorrow. He talked for a few minutes, then he stopped and looked around the room, choking on his tears. He took in every face and wiped his eyes before he continued. Straightening, he composed himself, and a tinge of menace crept into his voice. ‘I didn’t know him,’ Alan said. His voice was brittle. But this person is calling himself my son. He must have inherited my genes, because there’s no part of my beautiful Carrie in him. These girls—Carrie, Lorraine, and sweet, funny little Belinda—they were my family. They’re gone, Iris too. And the world is empty. There aren’t any guidebooks for burying your babies. Just a hole you fall into. I wish he’d taken me instead.’

‘He will,’ somebody whispered. And in the stillness, it carried down the room. Nash swivelled his head to the sound, but it could have been one of four men on the third row.

Alan paused, shaken. ‘I know some of you blame me. Maybe you should. But if I’ve learned anything from this, it’s that silence doesn’t protect us. It only delays the damage. So I suppose it feels fitting, right here in the middle of my children’s funeral, to appeal to you,’ He cracked, stumbled, almost collapsed and held onto the dais to keep himself upright. He took a second before he could speak again, but when he did, his voice was stronger. ‘If any of you know anything at all, please come forward. And Travis Bernstein, if you can hear this, come and talk to me, man-to-man. I’m ready for you.’ He shook his head, gathered his eulogy, written on a sheet of paper and stepped down. Nash felt the words he’d spoken, and they hit him like a bruise that would take a long time to fade.

After the service, the mourners drifted to the cars, stopping to talk and reluctant to leave. Brown moved between them, handing tissues to crying women, ushering older guests away from the muddy grass. She helped Hilary down a short slope, her voice kind and low. Nash caught snippets.

‘Take your time. Don’t worry, I’ll help you into the car. Just do whatever you need to, to get through today.’

‘Have you got a gallon of brandy?’ Hilary asked.

‘Honey, that can be arranged.’

It was easy to forget that Molly could wrangle a suspect with one hand and comfort a grieving stranger with the other. She had a mouth with a mind of its own, but damn, she was good with people. Nash stayed in the background. They had officers everywhere, with guns, plans and blocked escape routes.

But as he looked at the tears and the broken hearts, he realised they couldn’t prepare for everything.

Where was he?

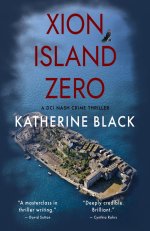

Xion Island Zero is book 6 in the DCI Nash series. They're all on KU. Hush Hush Honeysuckle is Book One, and this is the Amazon link.

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Behind the horses and two

Behind the horses and two black limousines, all funded by local business, Getaway Travel, people spilt from cars

Would that be the company run by the man with the famous writer for a a mother? : )

- Log in to post comments

You handled the funeral and

You handled the funeral and service so well Sooz. It captured my attention when someone whisphered; 'he will.' to Alan's remark of wishing he'd been taken instead of his family.

Keep going, I'm hooked.

Jenny.

- Log in to post comments

funerals are tough. Good sets

funerals are tough. Good sets to play out emotions. We' ve all been there. And we'll all be there. You're right . We vote with out bodies now. No priests or vicars. Celebrants. Right enough, the preists and vicars are dying out too.

- Log in to post comments