A Black Morris Minor and a Pink Carnation

By Turlough

- 1654 reads

A Black Morris Minor and a Pink Carnation

Had I closed my eyes I could have convinced myself that the glitzy disco funk group, KC and the Sunshine Band were performing live on the stage. I’m your boogie man, we were repeatedly reminded by the singer, a slight young man dressed in skin-tight homemade denim jeans and gold lamé jacket several sizes too big for him, as other highly sequined members of Prince Vijaya’s Caribbean All-Stars belted out note-perfect covers of sunshine hits from a variety of brass and percussion instruments. The band’s name was inaccurate as far as the geographical location was concerned, but Caribbean sounded so much funkier than Bay of Bengal.

A throng of party-goers sat at wooden bench tables spread with genuine plastic red and white gingham tablecloths. At the centre of each were faded plastic flowers arranged in jam jars with labels half removed, or a lit candle lodged in a wine bottle, but never both. These tables, probably the last surviving remnants of furnishings from great garden parties thrown by wealthy colonialists during the days of the British Empire, buckled under the weight of countless litre bottles of Lion Sub-Continental Lager chilling in ice buckets; proper ironmonger’s enamelled containers filled with shards of ice made overnight in those very buckets. Bemused geckos looked on from safe places on the walls as a solitary electric ceiling fan struggled under the weight of a fifty-year accumulation of cigarette smoke and dead flies, its motor stuttering as it choked in the acrid atmosphere that it was struggling to stir.

Dusky musky young brown-eyed women wearing diamante-encrusted hot pants and bikini tops barely sufficient to maintain decency tried to impress with Union Jacks painted on their fingernails in reddish, whitish and blueish correction fluid. Smiling at every male foreigner that went near them, and assuming they were all called Johnny, the bargirls would request cocktails from any who smiled back.

A miserably thin middle-aged European gripping a hideously fat cigar in his fifty-shades-of-brown teeth had a girl on each knee, each shrieking with false delight whenever his hands disappeared from view. I recognised him. As I recognised him, he recognised me. On a Scottish ship berthed in the harbour, I was the most junior member on the officers’ side of the business. I was a Navigation Cadet, or ‘gadget’ as the likes of me were jovially and cruelly referred to by the likes of him. He was the Captain. His lofty status meant that he was sourly referred to as ‘the Old Man’ by everyone of lower rank. In a working environment that could never be described as harmonious, he and I were the two individuals who despised each other the most. Had I been ten years younger I’d have probably said, ‘Well he started it.’

Had he uttered the sort of words he usually confronted me with he would have scared away his pretty lady friends, so instead he snarled the snarl of a thousand angry mongooses (or mongeese). To enable the snarl, he had to remove the cigar from his mouth which required disengaging one of his hands from a young woman’s buttock. This would really have made him angry. I knew the exact meaning of his bestial noises and it wasn’t pull up a chair and join us dear chap.

Merchant shipping companies didn’t send junior officers to exotic parts to enjoy themselves. They were there to work and to learn, but most of all to be bullied, just as this Old Man would have been himself thirty years earlier. A major feature of the nautical intimidation procedure was to bestow upon the junior cadet the responsibility for turning off the ship’s lights and hoisting up a few flags at that unholiest of hours otherwise known as the break of day. At that time of the year in Sri Lanka, success in meeting this daily demand required being on the ship and able to stand up at 5:30 a.m. Whether I’d enjoyed an evening of liquid merriment and funky disco dancing with shipmates at Colombo’s Three Stars Sports Club (known affectionately by music lovers and foreign seamen as the Tropicana) or not, having such responsibilities to fulfil never seemed like anything less than cruelty.

Flags needed to be raised at the sharp end and the blunt end of our surprisingly long ship (a 30,000 metric ton bulk carrier) as well as at the very highest point, so it was quite a hike with a lot of up and down the stairs bits at a time of the day when tropical heat was already starting to think about making life uncomfortable for anyone who had grown up somewhere as un-tropical as Leeds.

With that heat came a smell. A foul smell I’ll never forget. The air in most of the city carried the combined aroma of rotting vegetation and various other items of decayed matter that few sanitised Europeans would enjoy having wafted up their noses. This meze of nasal abhorrence emanating from a number of sources, so that it would get you no matter what way the wind blew, was something that no individual could be criticised for complaining about. Everybody suffered in some way. Posh people on a nearby P&O cargo ship, who paraded the decks in their brilliant starched white tropical uniforms with matching perfumed hankies fixed over their mouths and noses for protection from airborne bacteria failed to avoid falling victim. Even the flies, of which there were thousands, seemed feeble and lethargic.

Our vessel was moored at the quay belonging to the Sirimavo Bandaranaike Flour Mill, a state-owned concern named after the country’s prime minister who had been the first female in the world to be elected as a head of government. We were discharging a cargo of wheat that had been loaded in South Australia; a poverty relief shipment on behalf of the United Nations Development Programme. Six weeks earlier, in the Spencer Gulf, it had been dumped into the ship’s cargo holds by high tech machinery in the space of three or four days. Removing it from the ship at the other end of the voyage was a different story altogether.

Long pipes like fat cast iron drinking straws were inserted into the grain to pump it ashore where it would be transported from ageing metal hopper tanks to the flour mill via a series of rickety old conveyor belts that wouldn’t have looked out of place as exhibits in the British Museum. The equipment would regularly break down, or run out of fuel, at which point the back-up plan would come into operation. This entailed sending ten skinny little Sri Lankan fellas to sit amongst the wheat and scoop it into hessian sacks by means of old 800g-sized tomato tins. The filled sacks were then sewn up with hemp yarn at the neck by the overseer before ten slightly more muscular colleagues with worn ropes and calloused hands lifted them out onto the deck of the ship. At this point the proud operator of the Sirimavo Bandaranaike Flour Mill’s wheelbarrow would transfer the bags, each probably weighing as much as he did himself, to the quayside via the world’s most precarious plank of wood. There, the bagged cargo would be left for days for rats the size of wombats to gorge upon if not spotted by another port employee who held the responsibility for operating a long stick; the ultimate weapon in Third World vermin control. Further interruptions would come when it started to rain, making it necessary for cargo hatches to be completely closed. Heavy storms tended to arrive every afternoon at four o’clock for a duration of almost exactly forty minutes, just in time for tea and just as it was likely to have been during the days of the Raj in India.

Even when the overhead belts were working to full capacity, grain inevitably spilt onto the quay providing further sustenance for the rats. Such tasty morsels complimented their diets of porkpie-sized black cockroaches that ran amok during the hours of darkness. Even when these monster-like living fossils couldn’t be seen, we could always hear their skeletal bodies being crunched at by gluttonous rodents. Any dropped grain that wasn’t eaten, with the help of the regular heavy rainfall and intense heat, would either germinate or ferment where it had fallen and further enhance the already unsavoury fragrances that hung in the air or rose from the dock. I’ll spare you from a description of the contents of the dock.

Despite the torture that my soft, sensitive First World nostrils were subjected to, and the ridiculously early start to the working day, I quite enjoyed those tropical mornings wandering about the deck of the ship as the city of Colombo came to life. I literally saw the harbour wake up as piles of straw and sacking poorly concealed beneath parked trucks or in derelict warehouses, and sometimes in totally exposed spots on the sides of the roads, began to move. From these an army of yawning half-starved bodies emerged, hoping that the new day would provide food enough for them to get by.

I enjoyed being there when Captain Pugwash / Birdseye / Scarlet / Fantastic / McKinnon (delete as appropriate) rolled up majestically at the dock gates in a black Morris Minor taxi with a yellow roof. All the city’s taxis were of this make and model back then in 1976. His arrival would have been at a time late enough for him to have thoroughly enjoyed himself with his maidenfolk and early enough for his creeping aboard not to be noticed by any of the ship’s complement of officers and Jolly Jacks, or so he thought. It was probably foolish of me, but nevertheless satisfying, to cast a disapproving eye on him as he staggered up the gangway with a faded plastic carnation dangling from the back pocket of his jeans.

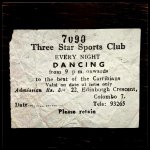

Image:

My own photograph of my own treasured souvenir. A ticket to admit one to an evening of dancing at the Three Star Sports Club in Colombo.

Next Part

Click on the link to read

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Fascinating view of the port,

Fascinating view of the port, and of the wheat management. I suppose if I'd thought of it at all I'd have thought of it neatly shrink-wrapped into huge cube bundles at the point of loading. Plastic saved, but removal long and complex! Rhiannon

- Log in to post comments

So full of glorious detail

So full of glorious detail that, as Schubert says, we can all smell it from here. Very much looking forward to those other parts, thank you Turlough

- Log in to post comments

Isn't it strange how much

Isn't it strange how much energy we have at the age of eighteen? Getting up so early and going to bed really late, managing a working day and still having the energy to enjoy the entertainment. Your description of the Three Star Sports Club I could see so clearly, I bet there was a lot of hanky panky and flirting went on.

Those big fat rodents reminded me of the time I worked on Avonmouth Docks for a company named BOCM SILCOCKS. we'd often see families of large rats coming up off the river avon and rumaging around in the warehouse looking for grain, they'd send shivers through me being so large and fast in movement.

Those poor Sri Lankens having to sit amongst the wheat. Then those cockroaches and the stench, along with the rodents sounds like hell...but I suppose if they never knew anything different and were used to it.

How long did you work on the ship? You must have had good sea legs and a stomach for the ocean waves. I take my hat off to you for the challenges you faced.

Jenny.

- Log in to post comments

Ha, ha! No tattoos for me I

Ha, ha! ![]() No tattoos for me I'm afraid Turlough. But I did love my job there and met many friends that I stuck with throughout my early life. Sadly most of them are dead now, but I often dream of them and wish I could return to those days.

No tattoos for me I'm afraid Turlough. But I did love my job there and met many friends that I stuck with throughout my early life. Sadly most of them are dead now, but I often dream of them and wish I could return to those days.

That's so impressive that you were working on ship for three years, I'm afraid I do get seasick even on ferries, which is a shame because I love the ocean and the calming lap of waves. Don't think I'd be much good on a rough sea though. Think I'd stick to the beach and just watch.

Thanks for replying to my comment.

Jenny.

- Log in to post comments

You are brilliant at

You are brilliant at descriptions! and you remember such details! I could not, even for yesterday. I feel very lucky to have read this. Also, silly for having commented before, that it was bad to have mechanisation if it made so many unemployed. Why was so much grain wasted, when so valuable? Did people not scoop it up to take home, if it spilled, or were they not allowed?

- Log in to post comments